By now you will have read that self-described 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four other alleged plotters will shortly have their day in court. Well, in a sort of a court, the kind where the rules have been made up on the fly (by Congress, no less!) and where convictions are all but guaranteed.

It is a system that may one day be operating not just in the confines of Guantanamo prison, but here in the USA, so we should all be paying close attention.

Here’s the background. President Bush set up the original military commissions by executive order on November 21, 2001. They were immediately condemned by the legal community at home and abroad, including the Committee on Military and Justice of the Association of the Bar of New York City.

Remember, this is only a few months after 9/11 and the New York City Bar is saying that the military commission system is an insult to both US law and international legal obligations. In his New York Timescolumn, conservative columnist William Safire denounced the commissions as “kangaroo courts.”

The more the legal community learned about what the Pentagon had in mind, the more convinced it was that military commissions could not dispense justice. The accused were to be deprived of trial by jury, and the open presentation of all the evidence. Hearsay could be introduced and the accused could be convicted by two-thirds of the 3 – 7 commissioners present. Civilian defense lawyers had to accept the fact that their conversations with defendants could be monitored by the military. There was no habeas corpus.

Then there was the issue of exactly how evidence was obtained. The White House had a dilemma. It needed to put in place a so-called legal system that would not, like the federal courts, be fastidious about accepting evidence obtained through torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, in violation of the Convention Against Torture, the federal anti-torture statute and the Constitution’s Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

While the Bush Administration endeavored to hide what exactly was involved in its “enhanced interrogation techniques,” that information was reaching the public. Shocking images from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq and the torture papers obtained through ACLU litigation put torture on the front pages, for awhile at least. The White House was meanwhile trying to keep its own internal critics at bay, as we recently learned when a State Department legal memo opposing the use of torture that had escaped efforts to hide the evidence was finally declassified.

In June 2006, the US Supreme Court in the case of Hamden v. Rumsfeld struck down the Bush commissions as unconstitutional. But they were given the kiss of life by Congress and vampire-like, they lived to see another day.

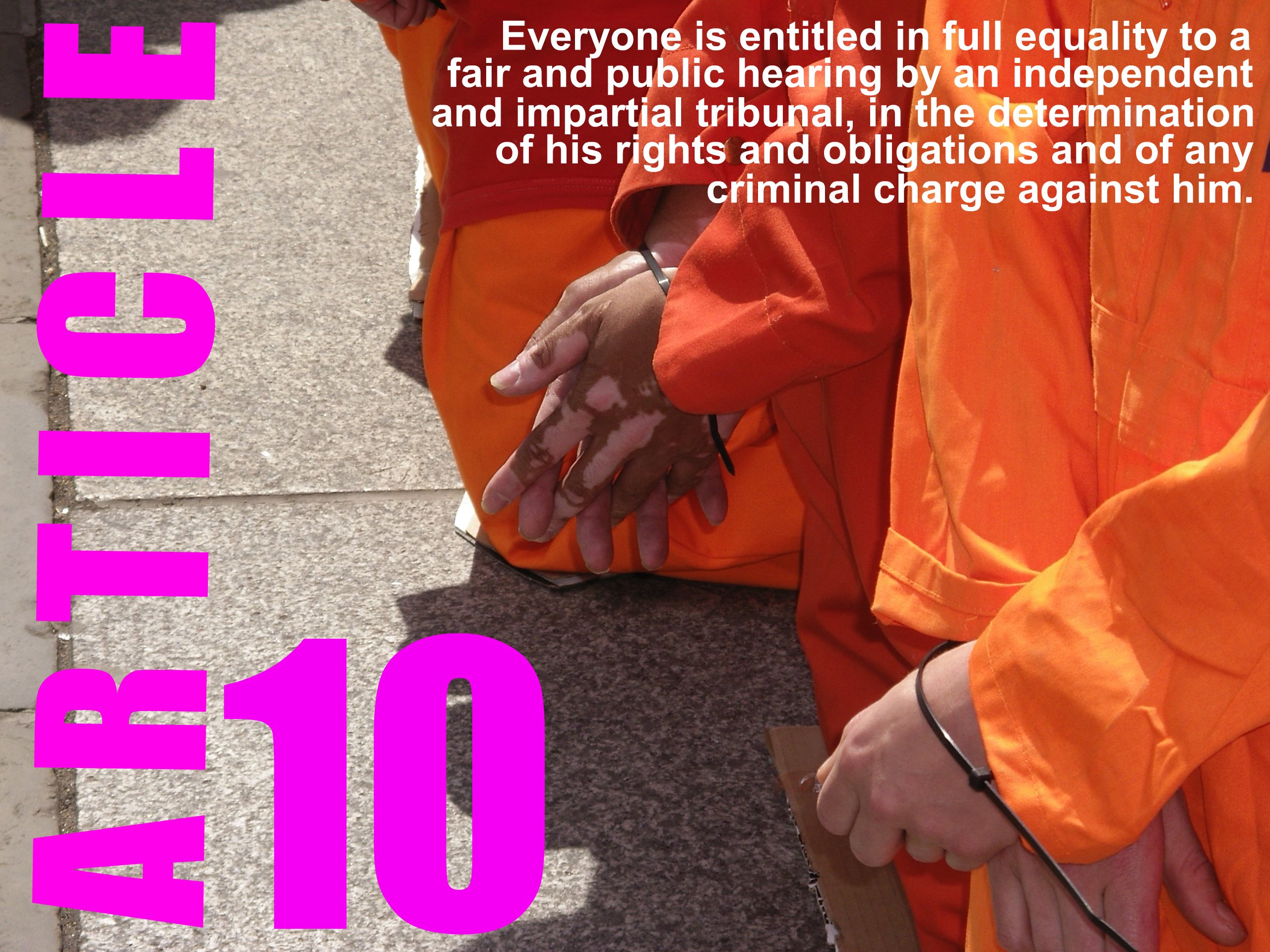

Photo credit: reprieve.org.uk

Among many other departures from US and international jurisprudence, the Military Commissions Act of 2006 – which was opposed by the entire Massachusetts Congressional delegation – allowed evidence that had been extracted through torture to be admitted, if it had been obtained before December 30, 2005, when the Detainee Treatment Act barring torture was passed.

Senator Obama voted against the Military Commissions Act, but in a speech delivered on the floor hinted at his future position. He opposed the bill not because it took terrorist suspects out of the federal court system, but because it was “sloppy” – and it was sloppy “because we rushed it to serve political purposes instead of taking the time to do the job right.”

The first case heard by a military commission involved the Australian detainee David Hicks. After an acrimonious session in which the presiding military judges barred two of Hicks’ attorneys from the courtroom and they countered that he was biased, it took just a minute for defense attorney Maj. Michael Mori to say that his client, who had spent five years at Guantanamo, pleaded guilty.

A few days after, a plea agreement was hatched in which Hicks would serve nine more months in custody in Australia. He promised to say he had “never been illegally treated” – although he had claimed previously that he had been beaten and given mysterious injections – and he promised not to “communicate in any way with the media” for a year.

“What are we to make of this?” ACLU attorney Ben Wizner wrote in the Los Angeles Times. “How did the very first case brought before a military commission – a system we were told was necessary because of the danger and impracticality of prosecuting arch-terrorists in US courts – result in a sentence of only nine months…it is widely understood that the government made extravagant claims that simply could not withstand scrutiny. No wonder the administration has fought so vigorously to deprive Guantanamo detainees of the bedrock right of habeas corpus – the right to challenge unlawful detention in court.”

The fact that Omar Khadr, the second detainee to be charged at Guantanamo, was only 15 years old when he was sent there did little to raise the stature of the military commissions system. Indeed, the system seemed on its way out after candidate Obama called them “an enormous failure” and then suspended them for 120 days on his second day in office.

But again Congress galloped to the rescue, this time to “do the job right” – or so the Obama administration would now have us believe. The Military Commissions Act of 2009 gave detainees the right to attend their trials and some leeway to choose their attorneys who would have an easier time getting access to classified information. Prosecutors do not have to reveal the “sources, methods or activities” by which that information was acquired.

Other tweaks made it harder to use hearsay, while not excluding it altogether. It is admissible if it appears “reliable under the totality of the circumstances.” Evidence obtained through torture is not admissible, but “information obtained through coercion that does not amount to torture” (definition please!) is fine. Although military courts traditionally try cases involving war crimes, the military commissions are empowered to try individuals on non war crimes charges, including conspiracy and providing material support for terrorism.

Another rub: it appears that detainees can still be detained even if they are acquitted by a military commission. As for convictions, it takes the agreement of two-thirds of the five – twelve commissioners present in cases requiring sentences for up to ten years. Cases involving longer sentences need three-quarters of the commissioners to agree. There must be unanimous agreement in death penalty cases and the approval of the president before an execution is carried out – as is expected to be the end result of the trials of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Waleed bin Attash, Ramzi Binalashibh, Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali and Mustafa Ahmad al-Hawsawi.

Here comes what David Shipler called the “dirty little secret” of the military commissions system:

Hardly anybody talks about it, but it’s a key reason for concern as the apparatus becomes establishes. It is this. The commissions can operate inside the United States, and they have jurisdiction over a broad range of crimes. Nothing in the Military Commissions Act limits the military trials to Guantanamo detainees, or to people captured and held abroad, or even to terrorism suspects. Nothing prevents the commissions from trying noncitizens, arrested inside the country, whom the president unilaterally designates as ‘unprivileged enemy belligerents.’

In other words, the law permits military officers to try non-Americans from Alabama and Arkansas as well as Afghanistan…once the commissions gain stature and become the ‘new normal,’ every future administration will have a ready instrument to arrest, judge and sentence wholly within the executive branch, evading the separation of powers carefully calibrated in the Constitution…If ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court, the elements of the military commissions will pass into the precedent of case law, creating a permanent apparatus, parallel to the criminal justice system, to prosecute and try foreign civilians. It could become a lasting injury of Sept. 11.

Eight months later, President Obama signed into law the National Defense Authorization Act of 2012, codifying indefinite military detention for anyone picked up anywhere in the world, including US citizens arrested in the United States.

Currently, as Shipler notes, the second-tier justice provided by military commissions is reserved for non citizens. But who is to say that in the next phase of the ‘new normal’ those annoying Constitutional rights governing the civilian court system won’t be dispensed with in cases involving citizen “terrorist suspects” as well?

Now that we are descending the slippery slope, anything goes – including the meaning of words. Check out the Pentagon’s new $500,000 military commissions web site. It is framed by the terms, “Fairness – Transparency – Justice.”